We write

great emails.

If you’d like to stay in the loop with the arts and creativity in Aotearoa, get ‘em in your inbox.

If you’d like to join a movement of people backing the arts and creativity.

An interview with Ruth Paul

We sit down with the 2019 Arts Foundation Laureate receiving the Mallinson Rendel Illustrators Award.

Congratulations on receiving the Mallinson Rendel Award for Illustration.

Thank you. The first couple of books I illustrated were for Anne Mallinson. When she set up with her publishing house in Wellington I illustrated a couple of books written by Vivian Joseph, whom she was publishing. It's a small world.

How did you feel when you received the call about winning the award?

I was very surprised, because you’re not comparing yourself to your peers, but to the standard that you'd love to get to worldwide. Which you will never get to. So when somebody gives you an award for being good at what you do, you think “but there's so much further to go!”.

It eases finances, which means you can put more time into what you're doing. But, I think the thing with artists is that the struggle is always with yourself and your ability to do the quality work you would like to see yourself doing. But the award is encouraging.

Your taste and your ideas change every year as you do, and what you want to achieve changes. I keep telling people, your best work is still out there, you haven't done it yet. Your next idea is your best idea, not your last one.

What made you start writing as well as illustrating books?

I think it's because you can have control over the whole arc of the story so you have more chance of creating a seamless picture book. It's an alchemy - a combination of things: the writing, the illustrations, the design, the concept, and production. You get to have more control over the various elements and create a more holistic work. When I write and illustrate, I can change a word when it's not working. I can change the illustrations when they’re not working. I can mix and matctell a story better by doing both.

Do you have any favourite authors, picture books or illustrators that have influenced you?

Late Sixties children's books influenced me. We had an influx of American books at that time, Dr. Seuss and Amelia Bedelia and there was this really great book called Tikki-Tikki-Tembo-No-Sa-Rembo by Arlene Mosel. It was the most unusual book becauase it was illustrated in this Sixties interpretation of willow pattern. It was about a Chinese boy who fell down a well, he had an enormously long name and they couldn't remember his name to pull him out. So the moral was don't have a name that's too long to remember. I haven't seen it since I was little, but I know there will be a copy locked up in the Wellington public library.

Do you think that it's the story, the illustrations or just a unique combination of the two that make a book successful?

I think it's very much the story as a whole, the concept or the idea. There needs to be something interesting that makes a kid want to find out what happens next. The more experienced I’ve become, the more I think it’s the integrity of the concept that counts.

What inspired you to write I Am a Jellyfish?

I started out with a story about a blob. And I thought a jellyfish would be great to call a blob, because nobody knows what they do or who they are, or what their reason for being is. But I then realised there was actually a blobfish and a Blobfish book already, so I couldn't do that.

I was toying with the idea of personality, of drifting and dreaming your way along, and questioning if it makes you a weak character if you don't know what your characteristics are. Jellyfish knows that she has something about her that's special, that’s strong, but she doesn't show it off to everybody all the time, it comes out when she’s challenged. But you'd read the book and you'd never know that's what I was thinking about it.

What inspires you to come up with a concept?

I’m constantly on the lookout, I couldn't live without having my antenna being alert to a good idea. The good ideas are fewer and more far between these days, because now I can tell when they’re good and I don’t waste my times with the bad ones. You can have a tonne of ideas, and most of them are crappy. But every now and then if a good one comes along, you're really aware that it's got bones and that you could do something with it. So I'd say the inspiration is less and less and the hard work is more and more, but I'm much faster at recognising a good idea when I have it. And sometimes it’s just the process - you start writing and you start drawing and through that something comes about, something that becomes a good idea.

Is every inspiration different?

Yes, it can be a million different things. It can be seeing something when you go for a walk, or talking to a friend. It can be a rhyme you trip over - the spark can be anything.

How do you manage to get a good idea down if you are not in the studio?

The great thing with picture books is they’re short. It's a short concept. It's a really contained idea. And the work is then writing it 35 different times in 35 different ways, with 35 different characters. You can spend a year writing something that you throw away, continually rewriting it, until you whittle it down to something really small. I'm sure heaps of people don't work that way. That's just the way I do it, come up with some kind of concept to explore and it doesn't always happen the first time.

That's quite a process to persevere with.

I think that most writers will tell you that they will really work something through. It's not that I spend every minute of that year writing that one story. I'll have five different stories on the go - three that I'm working on that are contracted, and one or two that are in development.

Then there's your other life. You need another life or you will go insane. You have to have a good work ethic. I'll get up and work in my studio most days, and meanwhile I have this other life where I live on a farm and plant trees. So when it drives me insane, I just go plant more trees.

You also need a community of people. I think I've really benefited from being part of the children's book community in New Zealand, because it's great having friends you can ring up and moan to when it's not quite working, or people to go out and have coffee with when you're going nuts.

What are some achievements in your career?

It's an achievement to have pulled off a book full stop, regardless of whether it succeeds or fails. A picture book is 30-plus illustrations. If you have an exhibition in a gallery, you can put your six great pictures at the front and hide three more around the back. But in a picture book, if just one of the 32 pages is weak, the whole book fails. If you read a picture book and go, “Eww look at that page,” it ruins it. That one word or picture will really annoy you, and you won’t read the I've taken on more work illustration, with characters looking and moving coherently. In my early days I found that hard to pull off. I’m better at consistency now.

Which of your books have been successful for you?

Stomp!, which is about dinosaurs playing follow-the-leader was a really simple fast idea, and sells like hotcakes. My first book The Animal Undie Ball also sold really well. It’s out of print now but I intend to update the illustrations and reissue it one day because it’s just classic at schools, it gets everybody up and laughing and running around. The King’s Bubbles has always sold well, and I am Jellyfish is turning over nicely. The best at the moment though is Little Hector – it’s walking out of the shop doors all by itself.

How many books do you complete each year?

In more recent times I've taken on more work, because one son has left home and one is still at home, but will go in the next couple of years. So now I can do two or three books a year. I'm illustrating the Mini Whinny series for Stacey Gregg and the Little Hector books are an ongoing series, there will be one of each of those for the next two years. And then there's whatever I've got in development at the moment. So maybe two or three each year.

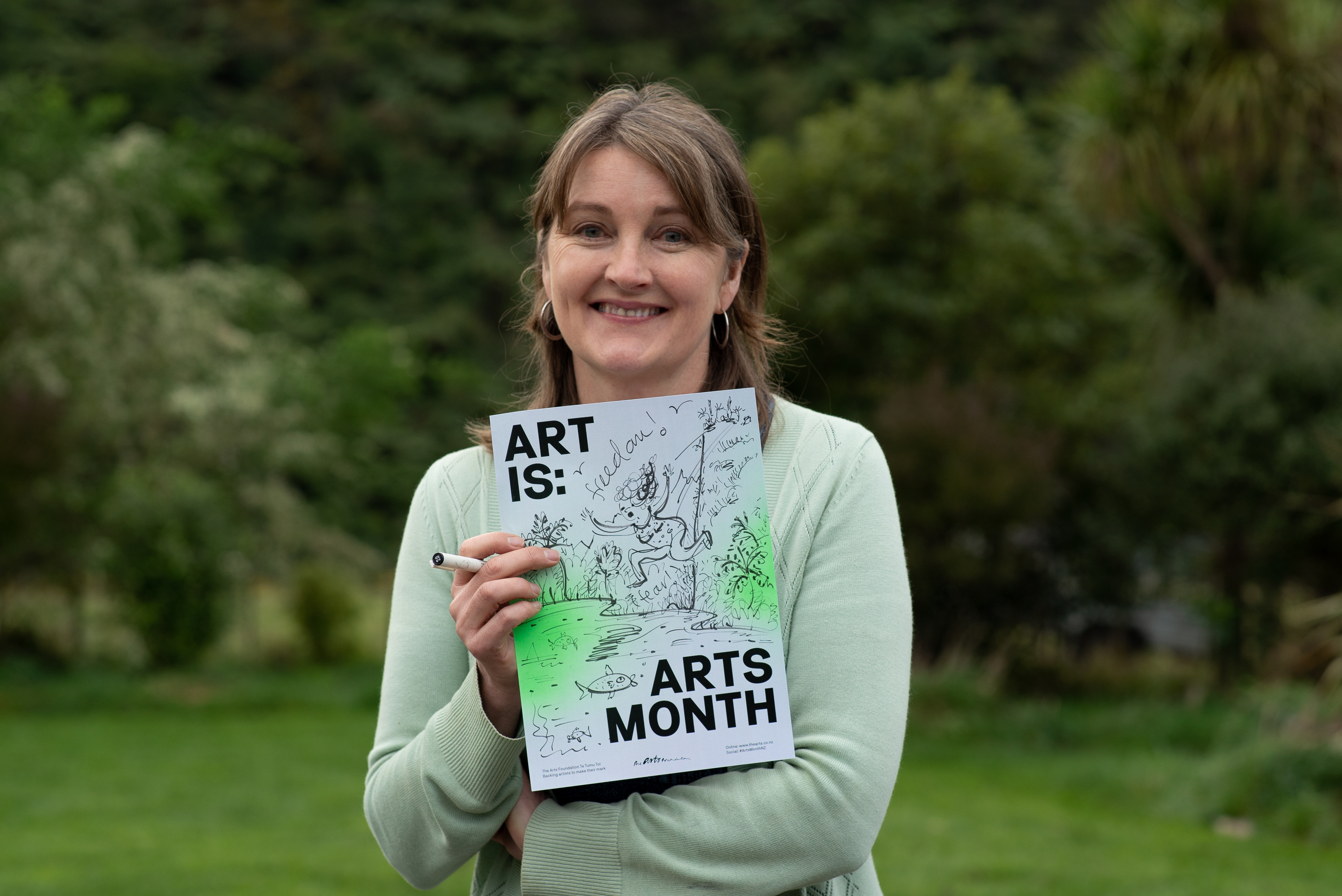

Ruth Paul, 2019 Arts Foundation Laureate receiving the Mallinson Rendel Illustrators Award

So when did you start writing and illustrating fulltime?

I was working as a commercial illustrator before I had kids. Then when my kids were born, 18 years ago, I started writing and illustrating my own books. I would have done one a year, until about four years ago. The quantity that I can produce has gone up over time so probably two a year since then.

So have you got anything coming up that you can talk about?

I've got a book coming out with Harper Collins in the US next year, a Halloween story called Cookie Boo! I’ve really enjoyed doing it because when you work with a huge company, they've an editor, an art editor, an editorial assistant, a massive team of people who comment on your work in develpment. They’ve so much time to put into your one little product, it's really great.

I've sold books in America before, but they were first published here, then onsold overseas. This is the first time I've worked with a publisher in America to publish there, and I've really enjoyed the process of developing the work.

I’ve worked with really great people here in New Zealand, especially Vida and Luke Kelly who often do the book design. But we're a much smaller industry here. So you're on your own a lot more. Once the publishers are confident that you know what you're doing, they leave you to it.

What’s the editorial process? Does someone give feedback on your work?

The editor works with the words. Once they’re decided, the art editor comes in and works with you on the visuals, the illustrations, the style, the characters and the layout. Sometimes they’re brought in towards the end of the book once you've supplied all the illustrations. It’s great when an art editor can work with you from concept onwards. They will say things like: “there's a wonky eye in this picture”, or “your character’s got one more finger in this picture”, or “can we change the perspective on this one?” The editors also know their market really well. They know the age group they're selling to, and what else they've got in their stable of books so they know how to differentiate your work from someone else's. I’ve found it a really satisfying experience.

Would you like to work with Harper Collins on more US books?

Hopefully, but I haven't got any work to a stage that I can show at present. To sell your stuff in that bigger market, you've got to have a full dummy copy, with the illustrations all worked out to a point where they can flip through and see what you propose the finished product might look like. In short, you have to do a whole pile of work before somebody might tell you it's a really stupid idea!

Agents are generally really good for that, they can probably say “I don't think this will work” and help you before you put in too much effort. So I have an agent now who's in the States. And the US has a really long lead-in. They buy your work three years out, so I sold Cookie Boo! to Harper Collins a year-and-a-half ago, and it doesn't come out till 2020.

Ruth Paul, 2019 Arts Foundation Laureate receiving the Mallinson Rendel Illustrators Award

The process is really fascinating. We pick up a book and we don't have any idea.

I still love reading a picture book, even though my kids have grown up. I fondly remember the bit where you cuddle up with them and read a book, and how important that moment is. If I ever feel bad about working, I remember that moment. That’s what it's about.

One thing we are scared of doing as authors, is leaving space in the work. Especially for younger kids, the more they can follow something with their finger and make their own noises and free-talk during the story, that’s where they make their own cognitive leaps between what happens from one page to the next. With an animation, you pop kids in front of the screen and the story is provided for them. But if you've got a book, they have to imagine what happens from one page to the next, because the images have changed and the words might not say outright. So in their brains, they themselves have to move the story to the next scene, they have to imagine the in-between.

Are there specific guidelines around how children learn and do you have to be aware of any theories?

No. And I'm really bad with grammar as well! If you work in educational publishing, I think you have to be aware of all that, you need to know what age you're writing for, their reading level and all that sort of thing. But with a picture book, there’s more freedom and the publishers will determine the market. You just have to write what you find fun and interesting.

Working with editors, what happens when they say “that eye is out of place”? Can you easily change it?

It depends what pictures I’m working on. If it's little changes like that, you can do them quite easily digitally. Often it will happen at the drawing stage, because you've got somebody commenting early on, you can scribble out a rough concept and they can change it before you put too much time in. So you always go through these stages - your roughs, your pencil roughs, and your colour roughs. During those stages they can stop the process and make changes and often you will completely redraw illustrations.

People think a picture book is a really straightforward thing. I'm sure people imagine I live like Beatrix Potter and have this lovely life drawing bunnies. But bunnies are really hard to draw, you know.

So you come up with an idea and it can take up to a year sometimes to develop it. Then you send the rough to an agent or a publisher, and then you've got this whole other process of several different illustration levels. It’s quite the process!

I’m working on something at the moment that I'm just about to send out. I've got to the dummy stage, but I had previously written and drawn it with another set of characters, I had a whole lot of lollies as my characters, and I did the whole book, thinking, this is a really hilarious idea. And it was a hilarious idea, and it did catch attention. But everybody said, we can't sell a book with lollies as characters, it's not going to happen. So I rethought the whole thing and did it with litter, which is a much better idea. But I had to redraw the entire book, all 32 pages, to make that concept work. So that would probably have been sitting around for two years now. And I've gone back to it and reworked it, and now it will go out again as a different thing.

But that's only the first stage, because then when a publisher accepts it, they'll go “This is hilarious, we love it, but now we're going to change the style,” and I will start from scratch again.

The irony of it is, that if I ever pick up a picture book where it looks like somebody has had to make an effort, or it looks labored, I hate it. I want to pick up a picture book that looks like it was just the simplest, easiest, most free-flowing thing, I don't want to know there was labour involved. Because you know, some books just look far too hard.

The other bummer is that some other writer might have a brilliant idea, write it in a day, whack out illustrations in a week and have it become a bestseller. In that case, everything I just said above is to be ignored.

What does the process of illustrating ignite for you?

I love the challenge of the work of a book. And I love the fact that out there - in my head - there is this elusive perfect picture book that I'm going to make one day. I probably won't, but that's the goal.

And you can get older with this job, and until I lose my hands or my eyes I'm only going to get better as I get older, which is nice to know, because many professions aren't like that. But forcing myself to sit down and work through the first lot of sketches for something or try and come up with a style that's suitable, I find all of that really hard. I do find the work really hard, quite a lot of the time.

Why did you become an artist?

Because I was really bad at math.

Art at school made me want to carry on with art. I did many millions of jobs in-between times, namely waitressing, before I went back to Polytech and studied illustration. I'm good at being my own boss. I know that I'm quite motivated when working on my own.

Is there anyone who influences you or mentors you?

Just every other picture book practitioner who I admire. I’ve a list as long as my arm of illustrators and writers whose work I love, far too many to mention. With the internet you're exposed to so much more work, it's got to be good because it raises your level of expectation when you see international work. I figure picture-booking is a craft, not just a commercial enterprise.

So has there been any pivotal moments in your career?

Having kids and understanding what it is to read a picture book, yes, that would be pivotal. To be the reader of them, as a practical thing, not an as an artist, reading them because I need to put my kids to sleep. That was really pivotal. And getting to the point where I didn't need a part-time job has helped as well. Becoming more financially stable has helped.

What is art to you and why does it matter?

The older I get, the harder it is to be impressed by anything. But when I see something that makes me feel emotionally alive, whatever that is - that's the art that I appreciate. It could be a fantastic illustration, or it could also be a kid’s show down at the local hall where the boy who gets up and tap dances breaks my heart. It's the thing that moves me away from everything I know and puts me in touch with an emotion whether that’s elation or sadness. In short, art is the human-made thing that moves me. Because in the busy-ness of life, I forget to be moved, and to be provoked by something another human being has made, not because they had to, but because they wanted to, that is an experience of freedom for me.